Aboard the Paramore today, it’s Halley’s 43rd birthday* and I thought I would celebrate it this year by writing about how I became interested in Edmond and the qualities that I like about him.

My interest began in the summer of 2010 when I visited the Royal Society’s 350th anniversary exhibition. I very much enjoyed the exhibition and it inspired me to read a couple of biographies of Isaac Newton, about whom I then knew very little – but while I found Newton a fascinating character, it was Halley who stood out for me, because among such complex and difficult men as Newton, Hooke and Flamsteed, Halley shone out as well-balanced, well-adjusted and nice. [1]

His kindness and lack of envy at the achievements of others are, I think, most apparent in the part he played in the publication of Newton’s Principia and it’s that role that I’ll try to sketch today.

The story begins in January 1684 when the 27-year-old Halley met up with Robert Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren and discussed the nature of celestial motions. Halley said he’d concluded that “the centripetall force decreased in the proportion of the squares of the distances reciprocally” (the inverse square law**) but that he’d been unable to prove it; Hooke affirmed the law and claimed that he had proved it, but Wren apparently didn’t believe him and so offered a book of 40 shillings to whoever was able to give him a convincing demonstration within the next two months.

The prize was never claimed, and in Halley’s case he may have given it little further consideration as he was shortly afterwards beset by several domestic crises. First, his younger brother Humphrey died abroad, then on March 5 his father went missing and five weeks later was found murdered on the banks of the Medway, then about the middle of March, Halley’s wife Mary gave birth to a daughter, Katherine, who was not to survive. [2] And if all that wasn’t enough, Halley’s father died intestate and a legal war immediately broke out between Halley and his stepmother that would rumble on for almost fifteen years. In the circumstances, it was unlikely that Wren’s challenge was at the forefront of Halley’s mind.

However, in August 1684, while probably engaged on family business in the area, Halley remembered the celestial problem and decided to visit Isaac Newton in Cambridge, whom he’d met once before in London. After some pleasantries, he asked Newton what type of curve he thought would be described by the planets orbiting under the inverse square law, and Newton immediately replied it would be an ellipse – and that he had proved it. An astonished Halley asked to see the proof, but Newton said he couldn’t find it but would redo the demonstration and send it to him.

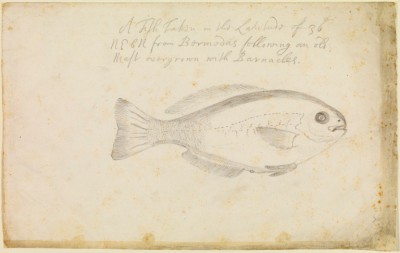

Halley resumed his attendance at Royal Society meetings in November, having been absent during his domestic tribulations, and on December 10 reported that he’d seen Newton again in Cambridge, who had “shewed him a curious treatise, De Motu, which, upon Mr Halley’s desire, was, he said, promised to be sent to the Society to be entered upon their register.” This paper would develop into the three-book Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica over the next 18 months, a period during which the Society was preoccupied with the publication of De Historia Piscium (History of Fishes), an impressive but poorly-selling book by Willughby and Ray, and Edmond and Mary welcomed a new daughter, Margaret, into their world (April 1685).

On 27 January 1686 Halley was elected to the new post of clerk to the Royal Society, defeating 3 other candidates (including Hans Sloane) despite not meeting some of the specified criteria (he was not a single man without children, and didn’t reside in Gresham College where the Society met) but the Society had reserved the right to waive any of the qualifications should they wish to do so.

Now it used to be thought that Halley was in severe financial difficulties after the death of his father and that that was why he’d sought the subordinate post of clerk with a salary of just £50pa, but Alan Cook has shown that Halley had a moderate private income of about £150-200pa from his father’s estate, (Flamsteed’s salary as Astronomer Royal was £100 and Pepys’s £350 as Clerk of the Acts, although Halley also had children to support), and so his interest in the position probably derived more from his interest in the Society and its activities than in the attendant salary. [3]

With Halley now employed as the Society’s clerk, the next we hear of the Principia is on 28 April 1686 when Dr Nathaniel Vincent presented “a manuscript treatise intitled, Philosophiae Naturalis principia mathematica” to the weekly meeting, where the Fellows agreed to refer consideration of printing the book to the next Council meeting. But the Council didn’t meet again when expected and so at a regular weekly meeting on May 19, the Fellows agreed to go ahead and print the Principia at the Society’s charge – a decision that may have been pushed through by Halley. This didn’t go down well with the Council, not least because the Society’s finances were reeling from the cost of De Historia Piscium, so at the next Council meeting on June 2:

It was ordered, that Mr Newton’s book be printed, and that Mr. Halley undertake the business of looking after it, and printing it at his own charge, which he engaged to do.

So the ‘lowly’ clerk has to foot the bill!

It says much about Halley’s admiration for Newton’s work and his recognition of its importance that he agreed to pay the cost of publication (and edit, print and promote it), especially as it meant neglecting his own concerns and jeopardising his employment at the Royal Society. One wonders what Mary Halley thought about the matter? I said in a previous post that I tend to think of Mary as being very supportive of Edmond and it’s these events I had in mind as it strikes me as unlikely that Halley would have acted as he did without Mary’s support.

In any event, Halley’s troubles had barely begun. In April, his stepmother had taken him back to court over the settlement of his father’s estate, and at the Council meeting on June 16 (the one following that where he was ordered to pay the cost of printing the Principia) his employment as clerk was challenged on the grounds that he didn’t meet the qualification that the clerk be single and without children. However, the challenge was dismissed by the Council, since the Society had chosen to dispense with those requirements at the time of his election in January.

This attempt to remove him might have arisen because he was deemed to have overreached himself in apparently bouncing a regular meeting of the Society into agreeing to print Newton’s book – or it might have been launched by Robert Hooke as the Newton-Hooke priority dispute was by now well underway, and Hooke would have been unhappy with Halley’s support of Newton.

The priority dispute and handling the temperamental Newton (and Hooke) was another problem that Halley had to contend with. After the presentation of the Principia to the Society in April, the Fellows adjourned to a coffeehouse where Hooke claimed that Newton had taken the idea of the inverse square law from him. Halley, who seems to have grasped Newton’s personality very early on, was concerned that he might hear an overly dramatic account of Hooke’s claim from another source, and so wrote himself to Newton on May 22 giving a diplomatic report of the situation. Newton replied quite calmly on May 27 setting out what he recalled of his correspondence with Hooke, and then wrote again with further particulars on June 20.

But the ink was barely dry on that letter when what Halley had most dreaded now occurred, and another Fellow gave Newton an incendiary account of Hooke’s claim – and Newton duly exploded. He returned to his June 20 letter and added a postscript lambasting Hooke and threatening to suppress the third book of the Principia, its most important section and principal selling-point. Halley then wrote a masterly reply, judiciously constructed to pacify Newton and save the third book, which so far achieved its intention that Newton “wish[ed] I had spared ye Postscript in my last [letter]”.

Back at the Royal Society, Halley still wasn’t safe in his job. The June attempt to remove him had failed, but on 29 November 1686 we read that:

It was resolved, that there is a necessity of a new election of a clerk in the place of Mr Halley, and that it be put to the ballot, whether he be continued or not.

And at the next Council meeting of 5 January 1687, a committee was selected to examine the books and Halley’s performance – which reported on 9 February that the books and papers were “in a very good condition, and the entries made according to order”.

Shortly afterwards, Halley received a letter from Newton saying that he’d been “told (thô not truly) that upon new differences in ye R. Society you had left your secretaries place”, and Halley replied that all was well (!) but that “6 of 38, last generall Election day, did their endeavour to have put me by”. Halley then promised to do nothing else until Newton’s book was finished and on March 7 he wrote to say he now had a second printer at work on book 2 and that he would engage a third to print book 3 “being resolved to engage upon no other business till such time as all is done: desiring herby to clear my self from all imputations of negligence, in a business, wherin I am much rejoyced to be any wais concerned in handing to the world that that all future ages will admire”. However, his first printer was able to print book 3, having finished book 1 by that time, and on 5 July 1687 Halley wrote to inform Newton that the Principia was finally ready.

But Halley’s contribution didn’t stop there: he promoted the book to his correspondents in advance of publication; he composed an introductory Latin ode to the work; he reviewed it (anonymously) in the Philosophical Transactions; he distributed presentation copies (at his own cost) to key individuals; and he sent a presentation copy to King James II, accompanied by an essay written by himself on Newton’s theory of the tides, a subject carefully chosen by Halley to appeal to James, a former Lord High Admiral.

With his family misfortunes, his legal disputes, his work as clerk, his fight to retain his employment, his reading, editing and overseeing the printing of the Principia, and his management of the volatile Newton, Halley must have been under great strain throughout this period, yet he betrays no hint of that in his correspondence.

So did Halley receive any reward from the Royal Society for his hard work and the credit accruing to them from his publication of the Principia? After several applications by him to have his salary confirmed and paid (he’d received nothing after 18 months), on the 6 July – the day after the Principia was completed – the Council agreed to pay Halley a bonus of £20 in addition to the promised annual salary of £50, the whole amount to be paid to him … in the form of 70 unsold copies of De Historia Piscium, the very book that had prevented the Society from publishing Newton’s book in the first place. I doubt that Halley appreciated the irony.

Happy birthday, Edmond!

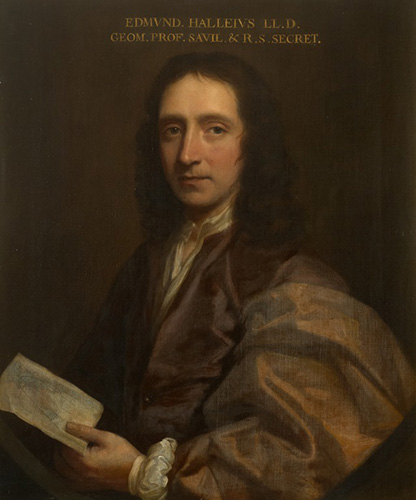

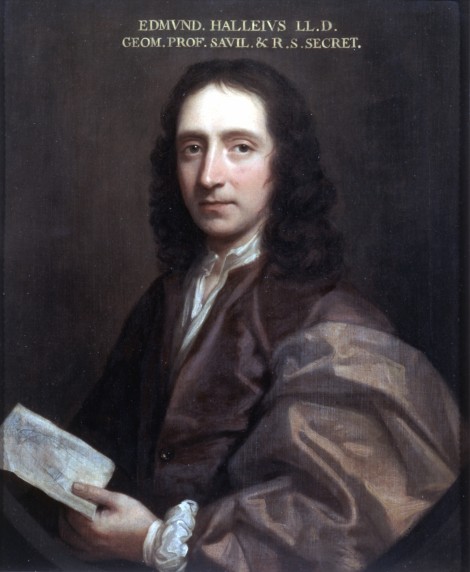

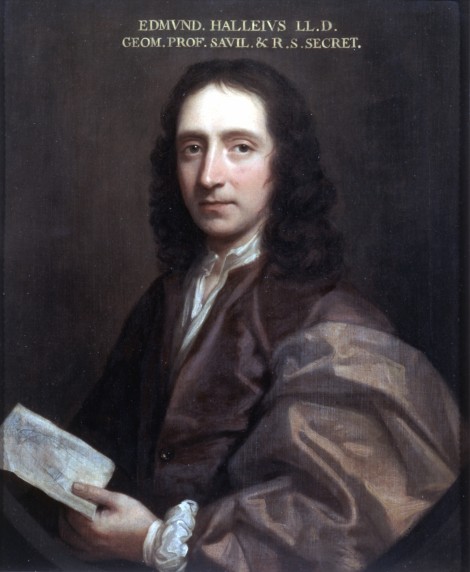

Edmond Halley in his early 30s (the inscription is a later addition). This is how Halley would have looked around the time he was publishing Newton’s Principia. (© The Royal Society (£), Image RS.9284)

* Halley’s birthday is 29 October (OS) or 8 November (NS)

** In essence, if two bodies move apart by 3 units the gravitational attractive force between them decreases by 9, if by 4, then by 16

_______________

[1] This was my early impression of Halley and I have encountered some less impressive behaviour since then.

[2] The date of Humphrey’s death isn’t known but is generally given as 1684 as Halley applied for administration of his estate in autumn of that year, and he is known to have died before their father. Katherine was baptised on 27 March 1684 but again the date of her death isn’t known, though she had certainly died by 1688 when the name was used for another daughter. If she died shortly after birth, it may be that Halley lost his brother, father and daughter in the space of a few weeks.

[3] The assessment of Halley’s income from his father’s estate can be found in: Alan Cook, Edmond Halley: Charting the Heavens and the Seas (Oxford, 1998), Appendix 3.

All references to Royal Society minutes are taken from: Thomas Birch, The History of the Royal Society of London…, Vol IV (ECCO print edition).

All quotations from Newton-Halley correspondence are taken from: HW Turnbull (ed), The Correspondence of Isaac Newton, Vol II (CUP, 2008 edition).