The Paramore anchored in St George’s Harbour, Bermuda, on Friday 21 June 1700 and Halley and his crew remained there for nearly three weeks. They were busy during that time, the crew careening the ship in order to clean her, and Halley taking the latitude and longitude of the island, observing the tides and coastal dangers, and buying a new stream anchor to replace the one they had lost at Barbados.

Before leaving the island on 11 July, Halley wrote an informative letter to the Admiralty in London, describing his progress during the last few months:

(Halley to ?Burchett, dated 8 July 1700 from “Bermudas”, National Archives ADM 1/1871 (not autograph))

Honourd Sr

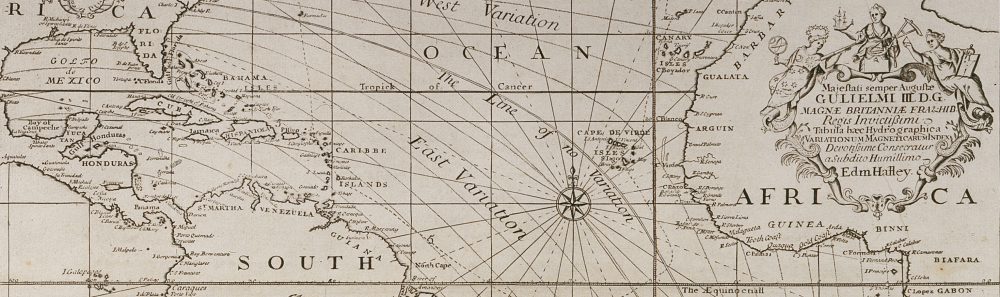

My last from St: Hellena, gave your Honour an Account of my Southern cruise, wherin I endeavoured to see the bounds of this Ocean on that side, but in Lattd. of 52°½ was intercepted with Ice cold and foggs Scarce credible at that time of the Year. haveing spent a Month to the Southwards of 40 degrees, and Winter comeing on, I stood to the Norwards Again and fell with the three Islands of Tristan da Cunha which yeilding us noe hope of refreshment, I went to St: Helena, where the continued rains, made the water soe thick with a brackish mudd, that when it settled it was scarce fitt to be drunke; all other necesarys that Island furnishes a Bundantley. at Trinidad we found excellent good water, but nothing else. Soe here I changed as much of my St Hellena water as I could, and proceeded to Fernambouc in Brassile, being desirous to hear if all were at peace in Europe, haveing had noe sort of Advice for near eight months, here one Mr. Hardwyck that calls himselfe English consull, shewed himselfe very desirous to make prize of me, as a pyrate and kept me under a guard in his house, whilst he went A Board to examine, notwithstanding I shewed him both my commisions and the smallness of my force for such a purpose, from hence in sixteen days I arrived at Barbados on the 21st of May, where I found the Island afflicted with a Severe pestilentiall dissease, which scarce spares any one and had it been as mortall as common would in a great measure have Depeopled the Island, I staied theire but three days, yet my selfe and many of my men were seazed with it, and tho it used me gently and I was soon up again yet it cost me my skin, my ships company by the extraordenary care of my Doctor all did well of it, and at present we are a very healthy ship: to morrow I goe from hence to coast alongst the North America and hope to waite on their Lordsps: my selfe within a month after the arrivall of this, being in great hopes, that the account I bring them of the variations and other matters may appear soe much for the publick benefitt as to give their Lordsps. intire satisfaction:

I am Your Hon:rs most

Obed:t Servant:

Edmond Halley

We’ve looked before at Halley’s encounter with icebergs, his stay on St Helena and his visit to Trinidad (modern Trindade), and read how Halley himself described being environed by “Islands of Ice” in the South Atlantic, but we can look now at some additional information concerning his arrest at Pernambuco and his illness at Barbados.

During his stay at Pernambuco Halley recorded In his logbook that:

Mr. Hardwick…desired me to call on him at his house this afternoon, where instead of Business he caused me to be Arrested, and a Portuguese Guard Sett over me … and I was given to understand that Mr. Hardwick had Acted in my Affair wth.out Authority being only impower’d to Act for the Affrican Company, and the Owners of the Shipp Hanniball wch. had been seized there as a Pirate and had no Commission of Consul

This “Mr. Hardwick” was one Joseph Hardwick who held the title of vice-consul in the city of Lisbon, from where the British envoy extraordinary, Paul Methuen, had given him authority to sail to Pernambuco “in Order to the takeing posession and remitting hither whatsoever remains there belonging to the ships Hanniball and Eagle which were Seized there last year [1697] by the Governours Order”. [1]

I haven’t had time to uncover the full story of the seizure of these ships but I noticed that Hardwick was specifically warned not to exceed his written authority, and so unless that authority had been extended in the two intervening years, I think that Halley was right to object that “Mr. Hardwick had Acted in my Affair wth.out Authority”.

The pestilential disease contracted by Halley and some of his crew at Barbados has not been identified, but a gastro-intestinal illness, yellow fever, and typhoid fever have all been proposed, the latter suggested by Halley’s remark in this letter that it “cost me my skin”. It’s interesting that he says that “it used me gently and I was soon up again”, because his log entries show that he was ill for quite some time, falling ill on 24 May and remarking that his strength was returning “but Slowly” on 5 June, which sounds like a lengthy illness to me. [2]

His doctor on both voyages was George Alfrey, whom Halley seems to have known before the first voyage as he specifically requested that the Admiralty warrant Alfrey to be his “Chirurgeon”, observing that Alfrey had “served in severall of his Ma:ties shipps for some years last past.” [3] And though not a fellow of the Royal Society himself, Alfrey apparently knew some of the fellows as he was in communication (as we shall see) with Hans Sloane and James Petiver. It’s possible that Alfrey died less than three years after this voyage ended, as there’s a George Alfrey, “Chirurgeon of Woolwich”, who died in 1703. I’m not sure it’s the same man, but two surgeons named George Alfrey in a maritime location seems fairly unlikely. [4]

In any event, Halley’s belief in Alfrey’s abilities seems to have been well-judged and it’s pleasing to read that “we are a very healthy ship” as Halley and his crew prepare for the homeward passage to England.

_______________

[1] Instructions to Joseph Hardwick, dated Lisbon 7 Feb 1698, National Archives, SP 89/17 Part 2, ff273r-27v.

[2] Norman Thrower mistranscribes this as “tho it used me greatly”, but the word is definitely “gently”. See Thrower, The Three Voyages of Edmond Halley in the Paramore 1698-1701, (Hakluyt Society: London, 1980) p 308.

[3] Halley to the Lords of the Admiralty, 21 Sept 1698, TNA, ADM 106/519/365.

[4] The contents of the will of the George Alfrey who died in 1703 (TNA PROB 11/471/222) don’t settle whether he was/was not Halley’s doctor and I have some slight doubt that it’s the same man as this one may only have been 22 at the start of Halley’s first voyage, which seems rather young for a surgeon who had served for “some years last past”.