Halley arrived back at Deptford on 10 October 1701 and immediately began to prepare his data for publication. He had undertaken the voyage with the aim of identifying a general rule for the complex tides of the Channel, and before he returned he had written to Josiah Burchett, Secretary to the Admiralty, to tell him that he had “discovered, beyond my expectation, the generall rule of the Tides in the Channell; and in many things corrected the Charts therof”.[1]

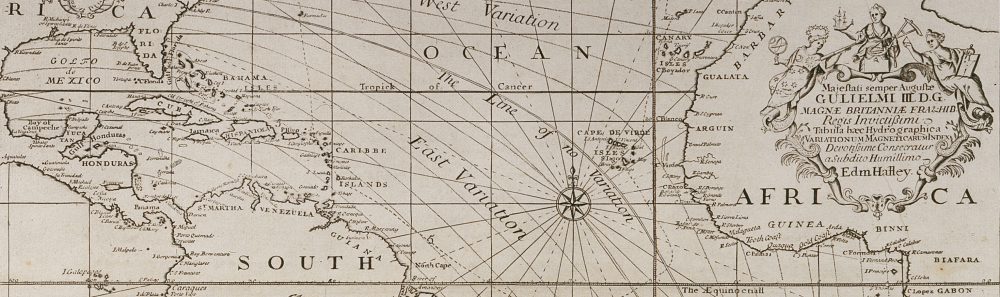

Halley had observed the tides and depths in the Channel, and surveyed the coastline and hazards, such as sandbanks and shoals. He again chose to publish his data in the form of a chart, and by mid-November he had a draught ready to show to a meeting of the Royal Society. Some time later, the chart was published by Mount & Page under the title, ‘A NEW and CORRECT CHART of the CHANNEL between ENGLAND & FRANCE: with considerable Improvements not extant in any Draughts hitherto Publish’d; shewing the Sands, shoals, depths of Water and Anchorage, with ye flowing of the Tydes, and the setting of the Current’, which left the prospective buyer in little doubt as to what he was purchasing.[2]

Western section of Halley’s Channel Chart (the inset maps appear on the eastern section). The original chart was probably published in 1702, and this version is no earlier than 1710, when Halley received his honorary doctorate (© Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) (£), Image No S0015918)

Halley’s chart resembles a portolan chart with its radiating lines, but it was an improvement on existing maps because Halley surveyed by taking angles from the rising or setting sun, rather than the more usual (but less accurate) magnetic compass. The chart has inset maps of the Isle of Wight and Plymouth Sound, and it records depths in fathoms around the Channel and ‘ye Hour of High-Water, or rather ye End of the Stream that setts to ye Eastward, on ye Day of ye New & Full Moon’ was indicated by roman numerals. Halley gave instructions to seamen on how they could use these figures to estimate the height of tides around the Channel, and he included his customary call to mariners to send him new data that could be added to future editions of the chart. The Admiralty were evidently pleased with Halley’s work as they again paid a bonus of £200 “as a reward to him for his Extraordinary pains and care he lately tooke, in observing and setting down the Ebbing, and Flowing, and setting of the Tydes in the Channell”.[3]

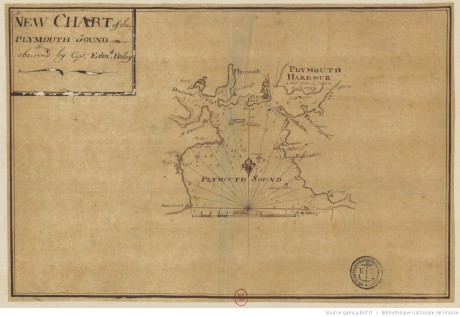

Manuscript version of the inset map of Plymouth Sound. The handwriting isn’t Halley’s, so it was presumably drawn by another under Halley’s direction (© Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Image No GESH18PF23DIV5P16D)

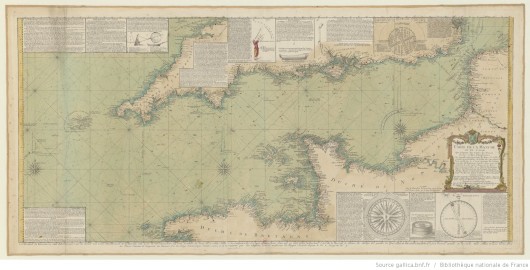

The chart was incorporated into pilot books and reprinted many times throughout the eighteenth century, both in England and on the continent (you can view several examples on the BNF’s Gallica website here), although Halley isn’t always credited as the source in later editions. Halley’s performance probably secured him the mission to the Adriatic, where he was sent by Queen Anne to survey the Imperial coast for the purpose of identifying a harbour where English ships could overwinter during the War of the Spanish Succession. Halley made two trips to the area in 1702 and 1703, and not only identified a suitable harbour, but also directed its fortification. Ultimately the Royal Navy did not need to overwinter in the area, but Halley’s work was rewarded by the support of the Secretary of State in the election for the Savilian Professor of Geometry at Oxford, where success brought Halley’s seafaring days to a close.

‘Carte de la Manche’ by the Chevalier de Beaurain ‘d’Après les Observations du Scavant Capitaine Haley’, 1778. Beaurain has added a number of insets on astronomical and navigational instruments (© Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Image No GESH18PF30P23)

This final post has been horribly delayed by what Halley would call “Domestick Occasions”.

_______________

[1] TNA, ADM 1/1872, 13 Sept 1701.

[2] In fact, this may not have been the title when it was first published: I’ve looked at several versions of the chart and they all seem to have a slightly different title and it isn’t clear which one was Halley’s original.

[3] Thrower, Three Voyages of Edmond Halley, p. 345.