Since leaving St Helena, Halley has sailed westwards in search of the islands of Martin Vaz and Trinidad*, an archipelago roughly 1,200km off the east coast of Brazil. They saw the three islands of Martin Vaz on the morning of 14 April 1700 and they reached the larger island of Trinidad (modern Trindade) on the 15th, anchoring on its west side.

They went ashore to look for water, which they quickly found, but then staved some of their cask on the rocky shore as they tried to get them back into the boat. The Paramore had drifted and so they stood further out to sea overnight on the 16th, and on the 17th:

This morning wee moored in 18 fathom on the west Side of the Isle, the north part being ENE, the South part SE, and the high Steep Rock like a Nine-pinn ESE.

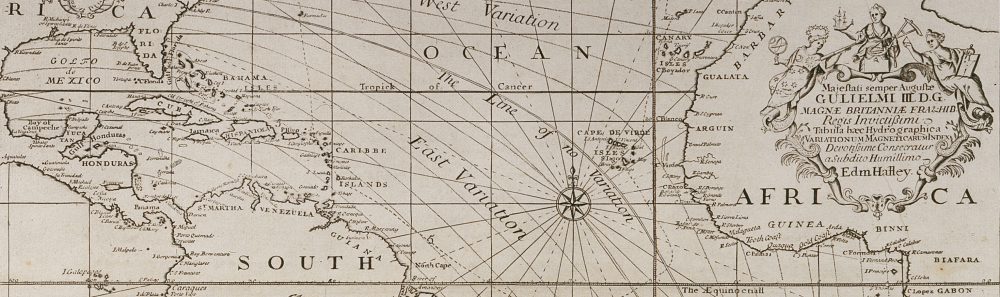

If you look at the west side of the map above, you can see the Ninepin rock near Bird Island, and a little further round the coast the word ‘cascade’ where they probably obtained their water. The east and north coasts are dangerously rocky, and while boats can land on the west, it’s not hard to imagine them staving their cask on the rocky shore.

The map derives from a book by Edward Frederick Knight, which details the second of two voyages he made to the island of Trinidad. He undertook the second voyage in 1889 in a ship named the Alerte to search for treasure (!), which he believed to be buried in the South West Bay – you can see his camp marked on the north of the bay. [1]

I haven’t read the whole book but it contains useful information relating to Halley’s voyage, especially regarding this next sentence in Halley’s logbook for April 17:

Whilest the Long Boate brought more Water on Board I went a Shore and put Some Goats and Hoggs on the Island for breed, as also a pair of Guiney Hens I carry’d from St. Helena.

In his book, Knight tells us that the best description of Trinidad he’s encountered is in the novel Frank Mildmay by Captain Marryat and that it is “easy to identify every spot mentioned in that book”. [2] Marryat writes of “the goats [and] wild hogs, with which we found the island abounded” and that on the summit they saw a herd of goats, including one “as large as a pony”. [3]

But Knight himself writes:

We saw no goats or hogs, and I am confident that none are now left alive. We did, however, in the course of our digging discover what appeared to be the bones of a goat. It is well known that these animals once abounded here. Captain Halley, of the ‘Paramore Pink’,… landed on this island April 17, 1700, and put on it some goats and hogs for breeding, as also a pair of guinea-fowl which he carried from St. Helena. [4]

He also mentions that an American commander, Amaso Delano, visited the island in 1803 and found plenty of goats and hogs, and then speculates that the “teeming land-crabs” have now “gobbled all these up”. [5]

Knight seems pretty unimpressed by these land crabs (“a loathsome lot of brutes” with a “cynical and diabolic expression”) but Halley doesn’t mention them at all. [6]

Halley’s final remark for April 17 is, however, extremely interesting:

And I tooke possession of the Island in his Majties. name, as knowing it to be granted by the Kings Letters Pattents, leaving the Union Flagg flying

This act of planting the Union Flag on Trinidad prompted a minor diplomatic incident nearly 200 years later. The island seems to have had a more lively history than can be covered here, but it was ‘discovered’ by the Portuguese in the sixteenth-century, visited by Halley in 1700, declared a principality by a self-styled prince in 1893, and then on 24 July 1895, a Times reporter writes from Rio de Janeiro that:

There is growing excitement here about the British occupation of Trinidad Island. The Brazilian Government has sent two notes to the British Legation emphatically protesting against the occupation… [7]

The British wanted it as a convenient station for transatlantic cables and apparently they based their claim on Halley’s visit:

Reuter’s Agency is informed on good authority that the British title to Trinidad Island dates from 1700, when it was taken possession of by Dr. Halley… [8]

Two weeks later The Times gave more detail about Halley’s visit during his “celebrated scientific cruise” in the “strangely named sloop the Paramour Pink” and noted that he was “said to have left some pigs and sheep [sic] behind him, but after an unsuccessful struggle for existence they succumbed to inanition or the land crabs.” [9]

It seems that no public claim of ownership of Trinidad had been made by Brazil since gaining independence from Portugal, but Britain was “ready to discuss in a friendly spirit” any claim that Brazil may wish to assert, and suggested the issue be resolved through arbitration. Portugal acted as arbiter and Britain peacefully accepted her ruling in favour of Brazil.

Perhaps the disappearance of Halley’s hogs had made it suddenly seem that much less attractive?

* These islands are now known as Arquipélago de Trindade e Martim Vaz and are not to be confused with the West Indies island of Trinidad. Trinidad is the spelling used for Halley’s island in all the original texts cited in this post.

_______________

[1] EF Knight, The Cruise of the Alerte (London, 1890), p 185. Chapter IX is actually called ‘Treasure Island At Last’.

[2] Ibid, pp 204 and 209.

[3] F Marryat, The Naval Officer; or, scenes and adventures in the life of Frank Mildmay (London, 1829), pp 209-210.

[4] Knight, The Cruise of the Alerte, p 173.

[5] Ibid, pp 170 and 173.

[6] Ibid, p 165.

[7] The Times, Thurs 25 Jul 1895, p 5.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Times, Tues 6 Aug 1895, p 7.

Pingback: Giants’ Shoulders #71: The better late than never, crack of doom, almost didn’t make it at all, sometimes life is like that, SNAFU edition. | The Renaissance Mathematicus