In a previous post I mentioned that while Paramore had been purposely built for Halley’s voyage, Halley was not her first commander – that person was none other than Peter the Great!

In 1696 Peter became sole ruler of Russia after the death of Ivan, his half-brother and joint-Tsar, and immediately began a grand project to modernise his backward country.

By the end of the year, preparations were under way for a Great Embassy that would travel through Europe recruiting allies against the Turks and studying western technologies. But what would be remarkable about this Embassy was that Peter himself would be part of it – not as its head, but as a private individual.

Peter was intent on travelling incognito to avoid the formality that would otherwise attend him and so he could work and move around like an ordinary citizen – though at 6 feet 7 inches tall, the Russian monarch was fated to stand out no matter how ‘ordinary’ he endeavoured to appear.

The Embassy left Moscow in March 1697 and travelled through northern Europe, arriving in Holland by mid-August. Here, Peter worked in the dockyards at Zaandam (where local boys threw stones at him) and at Amsterdam, but while Peter was impressed with Dutch ships, he was dissatisfied with their method of building them, finding they relied more on intuition and accumulated expertise than on mathematical precepts that Peter could learn and take back to Russia.

He was advised to visit England, where “this kind of practice is raised to the same perfection as other arts and sciences, and might be learned in a short time” [1] and so when William III (who was eager to cultivate Peter in order to secure certain trading rights for English merchants) invited Peter to visit England, Peter promptly accepted.

The main part of the Embassy stayed in Holland, while Peter and 15 companions set sail for England aboard HMS Yorke, flagship of Vice-Admiral Sir David Mitchell. It is said that Peter spent the voyage dressed as a Dutch sailor, and that he climbed to the top of the rigging, although he was unable to persuade the Admiral to climb aloft with him. [2]

The party arrived in London on January 11, and Peter initially resided in Norfolk Street, which ran between the Thames and the Strand (roughly where Temple tube is today), and it was here that Peter’s pet monkey is said to have startled William when it jumped on him during the King’s informal visit shortly after Peter’s arrival. [3]

But Norfolk Street wasn’t private enough for Peter and so in early February he moved his entourage south of the river to Sayes Court in Deptford, away from the intrusive curiosity of the London crowds and next door to the dockyards where Peter could continue his studies in shipbuilding.

Sayes Court was owned by the diarist and Fellow of the Royal Society, John Evelyn; it was a beautiful house admired by all people of taste, not least for its celebrated and influential garden. Evelyn had let the house to John Benbow in 1696, shortly after Benbow’s promotion to the rank of Admiral, but Evelyn was soon complaining of the “mortification of seeing every day much of my former labours and expense there impairing for want of a more polite tenant.”

Oh dear. If Evelyn was dissatisfied with Benbow as a tenant, he was in for the shock of his life when his property was sub-let to the Czar of Muscovia. The destruction wrought by the visiting Russians on Sayes Court during their two-and-a-half months’ stay has passed into legend. Benbow sued the government for compensation, and the assessment by Sir Christopher Wren of the damage done to goods, buildings, and Evelyn’s cherished garden amounted to £350 9s 6d – more than seven times Halley’s annual Royal Society salary. [4]

Peter didn’t restrict himself to destroying one of England’s finest manor houses, her sailing vessels caught his attention too. On 7 March 1698, a letter from the King’s dockyard informed the Admiralty that:

A Little Yacht Called ye Dove wch: is hired from William Charlton of Greenwich to Waite on ye Czar of Muscovia and he goeing down to Woolwich … his Ma[jes]ty Steering himselfe run aboard one of ye Bomb Vessells wch Broake away ye knee Cheekes Figure Railes and all yt belonged to ye head… [5]

And a month later, on April 13th:

The Dove Yacht wch is hired from Mr Charlton of Greenwich to waite on ye Czar of Muscovia has Sustained such another Damage as I gave yo[u]r Hono[u]r An Acco[un]t of ye 7th March past, by his own Steering Run on board ye Henrietta Yacht in turning up ye River wch broak away all her head and shook the Vessell very much, and has caused her to be very Leakey. [6]

Bravo! Peter’s appetite for life was insatiable and he was rarely at rest between these impressive navigational displays. He visited the Mint at the Tower and the Observatory at Greenwich; he watched a mock battle off Portsmouth and a night-time gunnery display at Woolwich; he had an affair with an actress and walked under the outstretched arm of a giantess without bending; he drank copious amounts of hot pepper and brandy, and famously ate out a tavern when he tarried in Godalming.

And amid all this, Peter might possibly have met Edmond Halley.

Halley’s entry in the Biographia Britannica tells us that:

[Peter] sent for Mr Halley, and found him equal to the great character he had heard of him. He asked him many questions concerning the fleet which he intended to build, the sciences and arts which he wished to introduce into his dominions, and a thousand other subjects which his unbounded curiosity suggested; he was so well satisfied with Mr Halley’s answers, and so pleased with his conversation, that he admitted him familiarly to his table, and ranked him among the number of his friends… [7]

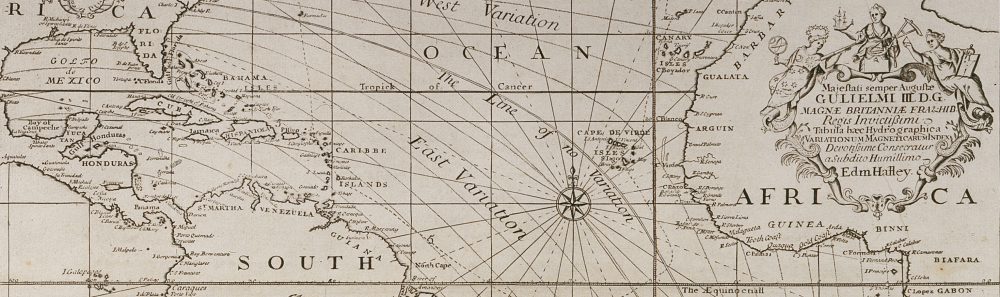

There is no known contemporary source that confirms their meeting and historians of Peter seem to regard this tale as part of the mythology that (unsurprisingly!) attaches to Peter’s visit to London. Yet none of the sources I looked at* mentioned the documented event that seems to offer the most likely indication that Peter and Halley met: Peter’s use of Halley’s ship Paramore.

In a letter dated 16 March 1698, the Admiralty writes to the Navy Board that:

The Czar of Muscovy having desired that his Matis Pink the Paramour at Deptford may be Rigg’d and brought afloat, in Ordr. to make Some Experimt. about her Sayling, We do therefore hereby desire & direct You … to give the necessary Orders for Rigg:g and bringing afloat the Said Vessell, & Employing her in such mañer as the Czar Shall desire…[8]

Order to rig the Paramore for the Tsar (© National Archives (£), ADM 2/178)

Now what’s interesting about this letter is that it says that Peter himself asked for Paramore to be brought afloat for his use, whereas the other vessels he employed all seem to have been proposed by the Admiralty: could it be that Peter made this specific request after meeting Halley, who perhaps talked to him about his ship? Halley’s diplomatic personality and nautical expertise would certainly seem to fit well with Peter’s character and maritime interests.

The semi-official Journal of the Great Embassy does not mention Halley but has entries for only 52 of the 105 days that Peter spent in England, and not everything that Peter is known to have done is recorded there. Peter might not have met Halley, but it seems to me just possible that he did.

And the story that Halley was one of those said to have pushed Peter through John Evelyn’s prized holly hedge in a wheelbarrow? Oh, now that’s undoubtedly mythical!

* ie sources which focus on Peter rather than on Halley – and there may be some that do mention Paramore beyond those I had time to look at.

_______________

[1] Arthur MacGregor, The Tsar in England, The Seventeenth Century, 19 (2004) p 117

[2] Anthony Cross, Peter the Great through British Eyes (Cambridge, 2000) p 16; MacGregor p 118

[3] Cross, p 18

[4] Sam Willis reproduces the itemised lists of the damage done to Sayes Court in his book, The Admiral Benbow, pp 241-244

[5] National Archives, ADM 106/3292, f.54v

[6] ibid, f.57r

[7] Biographia Britannica, Vol IV (1757), p 2517

[8] National Archives, ADM 2/178, p 462