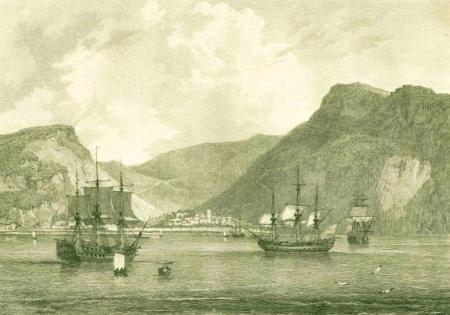

We last saw Halley encountering a storm as he sailed from Tristan da Cunha towards the Cape of Good Hope. A few days later he found the storm had blown him northwards of the Cape, and as his water supplies were low and he didn’t want to delay his voyage by heading back south, he decided to sail on to St Helena, arriving in Jamestown harbour on 12 March 1700.

I’ve mentioned before that one of the most disappointing aspects of Halley’s logbook is that he records very few observations about the places and peoples he encounters, and nowhere is this more frustrating than during his visit to St Helena – for this is not Halley’s first trip to the island, it was here that he acquired a Europe-wide reputation at the age of 22.

Halley was a nineteen-year-old undergraduate at Oxford when in July 1676 he sat down to write a letter to the Royal Society’s Secretary, Henry Oldenburg. He and Oldenburg had been corresponding about a paper that would be Halley’s first appearance in the Philosophical Transactions and after some remarks about his paper, he asks if Oldenburg knows whether a work then in the press at Paris would contain a catalogue of the southern stars because:

if that work be yet undone, I have some thoughts to undertake it my self, and go to St Helena… by the next East Indie fleet, and to carry with me, large and accurate Instruments, sufficient to make a good cataloge of those starrs, and to compleat the Celestiall globe… I will willingly adventure my self, upon this enterprize, if I find the proposition acceptable, and that the East Indie company will cause me to be kindly used there, which is all I desire as to my self, and if I can have any consideracon for one to assist me; this Sr I propose to you desireing your advice as to what inconveniences there may be, and if you think my design may meet with sutable encouragement. [1]

The young and ambitious Halley was concerned that with Flamsteed, Hevelius and Cassini all at work on star catalogues, there would be no room for him to make his mark, and so he decided to travel to the southern hemisphere to map the stars that were not visible from Europe and which had so far received little attention from astronomers.

His design did meet with “sutable encouragement” and through the influence of his patrons, Sir Jonas Moore and Sir Joseph Williamson, a letter was sent from the king to the East India Company requesting that they give free passage to Halley and his friend James Clerk on their next ship to St Helena, which at that time was under the Company’s governance.

Halley left Oxford without taking his degree, and he and Clerk sailed from England around Edmond’s 20th birthday on board the East Indiaman, Unity, arriving at St Helena by early February 1677. Halley tells us he took a newly made sextant, a new pendulum clock, an old quadrant, and several telescopes including his 24 footer, and on arrival he and Clerk began building a basic observatory from which to deploy them. [2]

But matters didn’t progress quite as Halley planned, owing to the continually adverse weather. In November 1677 Halley wrote to Jonas Moore that:

such hath been my ill fortune, that the Horizon of this Island is almost always covered with a Cloud, which sometimes for some weeks together hath hid the Stars from us, and when it is clear, is of so small continuance, that we cannot take any number of Observations at once; so that now, when I expected to be returning, I have not finished above half my intended work; and almost despair to accomplish what you ought to expect from me. [3]

Oh dear, he’d travelled a long way to be thwarted by cloud-cover, but Halley wasn’t the type to be easily defeated and so to simplify the process and maximise the number of star positions he could observe, he based his own measurements on reference stars from Tycho Brahe’s catalogue, so that if Tycho’s star places (taken before the advent of telescopes) were rendered more accurate in the future, his own positions could be accordingly adjusted.

By the time he and Clerk left the island in March 1678 on board the Golden Fleece, Halley had observed 341 stars, as well as a lunar and a solar eclipse, and a transit of Mercury – and by the autumn he’d produced a catalogue of his results (published the following year), which was the first to feature observations made using telescopic sights. [4] Halley also produced a planisphere – possibly engraved by his companion, Clerk – in which he outlined a new constellation Robur Carolinum (Charles’s Oak), named to mark the occasion when King Charles had hid in an oak tree after his defeat at the Battle of Worcester.

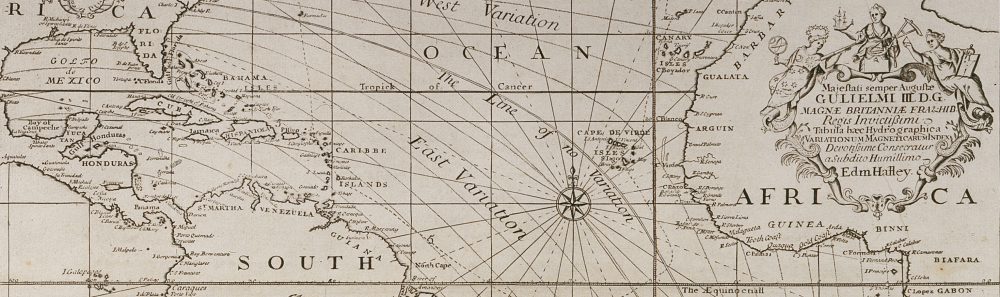

Halley’s planisphere of the southern stars. Robur Carolinum is right of centre below the Centaur’s hooves (© NMM, Image B4225). The work was engraved by a James Clerk, possibly the friend who accompanied Halley.

The catalogue and planisphere were well-received, with Flamsteed dubbing Halley “our Southern Tycho”, and Halley was rewarded with an MA by royal mandate, election to the Royal Society, and the esteem of Europe’s foremost astronomers. [5]

* * * * *

Now Halley is back on St Helena, scene of his youthful adventure. What went through his mind as he sailed into Jamestown harbour? Did he enquire after his former acquaintances? Go in search of the observatory built with his friend over 20 years earlier? Did he reflect on the path his life had taken since that first visit? He gives us no hint whatsoever, he tells us only that it rained heavily. Plus ça change.

If anyone from St Helena can advise whether Halley’s Mount is pronounced ‘Hawley’ or ‘Hallee’, please let me know via the comments. Thank you!

_______________

[1] Halley to Oldenburg, 8 July 1676, Royal Society EL/H3/38.

[2] The location of Halley’s observatory isn’t certain but there is a monument set up on what is thought the likely site on a ridge known as Halley’s Mount. You can see the monument here and the wider view here (the walls are probably from a later construction).

[3] Halley to Moore, 22 November 1677, in MacPike, Correspondence and Papers of Edmond Halley (London, 1937), pp 39-41.

[4] Halley, Catalogus Stellarum Australium (London, 1679); it was subtitled (in Latin) Supplement to the Tychonic Catalogue. The transit of Mercury on 28 October 1677 gave Halley the idea (subsequent to James Gregory) that a transit of Venus would be the most useful method of estimating the sun’s distance from the earth, a method he would later vigorously promote to those future astronomers who would be alive to observe the late C18 transits.

[5] Flamsteed, The Doctrine of the Sphere (London, 1680), Preface. How Flamsteed must later have regretted this remark! The context of it was more complex than can be covered here, but we might look at the toxic relationship between Halley and Flamsteed later this year.

Pingback: The Sir Hans Sloane Birthday Collection: Giants’ Shoulders #70 | The Sloane Letters Blog

It is pronounced as hallee on St Helena not Hawley

Thanks very much, John. I read somewhere it was pronounced Hawley there, and I’m quite pleased to hear that it isn’t, as I’d rather find support for the Hallee pronunciation than the Hawley (though I wonder if the pronunciation might have changed over time?). I’ve come across contemporary support for both pronunciations, but I suppose that we’ll never know for sure.

Sorry if this is not the right place for this sort of request, but can you recommend any good biographies of Halley? (Preferably still in print, but that’s not essential.)

Hi David, thanks for getting in touch. I list the main biographies of Halley on the Sources page (top menu), but they’re mostly out-of-print (and out-of-date!). Alan Cook’s is the standard bio, and by far the most accurate, but the style isn’t as enjoyably readable as we tend to expect from biographers today.

Your query has reminded me that I need to add another recent bio to the list; it’s by John and Mary Gribbin and called ‘Out of the Shadow of a Giant’ and deals with both Halley and Robert Hooke. There’s nothing new on Halley, but it’s a readable survey of his life and science. Roughly 2/3 of the book is on Hooke (we know far more about him), who was a key player in the Royal Society at that time. The book is very anti-Newton, though, which rather undermines it in my opinion. Both Hooke and Newton were exceptionally clever but difficult men, and they didn’t get on, but it’s a pity the Gribbins chose to big-up Hooke by trying to diminish Newton – it’s possible to admire (and criticise!) both.