Hello and welcome to Deptford, where Giants’ Shoulders #63 is coming to you LIVE from HMS Paramore under the command of Edmond Halley, astronomer, mathematician, geophysicist, meteorologist, cartographer, hydrographer, sailing enthusiast – and now Celebrity Guest Host of Giants’ Shoulders!

The captain is currently busy about the ship preparing to set sail on his second voyage, but he’s read and given a hearty yo-ho-ho! to all that’s new in the histsci blogosphere. So pour yourself a noggin of rum, break open the ship’s biscuits and dip into the captain’s treasure chest of ‘philosophicall’ bloggage.

(If you’re new to this blog, it’s about the voyages of Edmond Halley and accompanies the ‘live’ tweets of his logs, which explains the style of this carnival.)

The calm before the storm

We launch this 63rd edition of Giants’ Shoulders by taking a look at some snow – specifically, the Wrong Kind of Snow, which is the type proffered, according to Peter Broks, by those who usually haven’t read him. If that prompts history of science novices (like me) to review their foundational reading, then the list of introductory works recommended by Rebekah Higgitt in her interview with Riffle History is well worth consulting.

For the histsci professionals there’s another Wikipedia edit-a-thon at the Royal Society, focused on women in science, while John Stewart wrote about giving assignments in Wikipedia revision to his students at the University of Oklahoma.

James Brown at Cultures of Knowledge announced a new correspondence project, ‘John Collins and Mathematical Culture in Restoration England’, and Natalie Walters wrote about the hidden treasures of the Wellcome Library’s autograph letters collection.

The Wellcome Collection celebrated two anniversaries, that of Trust founder, Sir Henry Wellcome, and the opening of the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum in August 1913, while at the Science Museum Rupert Cole marked the publication 105 years ago of Geiger and Rutherford’s paper on a revolutionary new method of detecting particles.

We end this section by welcoming a new blog, Forbidden Histories, to the history of science blogosphere, it’s by Andreas Sommer and deals with science and the ‘miraculous’ – go take a look.

The line of battle

The reverberation from Steven Pinker’s broadside rumbled on with Steven Poole taking issue with Pinker’s language and “thinly veiled demand for total surrender by non-scientists”, and Leon Wieseltier likewise saw Pinker’s article as a demand that humanities submit to and be subsumed by the sciences. But Daniel Dennett considered Wieseltier’s piece “blustery” and warned you “can’t defend the humanities by declaring it off limits to amateurs”. Mano Singham noted ‘postmodernism’ is often used as a weapon by scientists against their critics, just as ‘scientism’ is used against scientists, while PZ Myers sought to rehabilitate postmodernism. In this time-travelling edition of Giants’ Shoulders, you won’t be surprised to learn George Orwell contributed to the debate.

Next up was a debate between Martin Rundkvist (prehistoric archaeologist) and Darin Hayton (historian of science) about the function of history of science. Rundkvist argued against ‘knowledge relativist’ history of science, where no comment is made about which of the historical participants turned out to be right, and Hayton responded that that was not history in any rigorous sense. The debate continued here (Rundkvist), here (Hayton), and here (Rundkvist), and was joined by a subsequent post from Thony Christie, arguing that history of science is history and not science.

Thony also stirred up extensive exchanges in the comments section of his post on what he regards as the good and bad of BBC history of science, and then offered a behind-the-scenes look at BBC programme-making with this illuminating interview with Lisa Jardine about her Radio 4 series, the Seven Ages of Science.

Dead reckoning

Ever wondered what a book bound in human skin looks like? Lindsey Fitzharris found out by handling this pocketbook bound in the skin of William Burke, one half of the murderous double-act, Burke and Hare. Perhaps anatomist Dr Knox should have stuck to anatomical models, such as these ivory models, whose history was investigated by Cali Buckley, or the papier-mâché models of Louis Auzoux, described by Brandy Schillace.

Another body-part to do the rounds was the bladder of one Mr Gardiner, examined by the Royal Society, Noah Moxham tells us, as part of their investigations into the efficacy of an alleged cure for bladder stones. But if you’re more concerned with the shape – or indeed existence – of your nose, this look at sixteenth-century rhinoplasty with Lindsey Fitzharris is well-worth sniffing out.

Burke and Hare reappeared in Brandy Schillace’s post challenging the notion that two man-midwives had been (anachronistically) guilty of ‘burking’ pregnant women. Elsewhere Jennifer Evans wrote about a man who claimed to experience physical responses similar to those of his wife each time she became pregnant. I wonder if the sight of forceps might have cured him of these sympathetic reactions, though as Brandy Schillace explains, even a labouring woman was unlikely to have seen the instrument, known for several decades as “the secret”. Mind you, when he wasn’t experiencing the physical responses of pregnancy, he was probably sharing the “Sweet and Benign Humours that Nature Sends Monthly”, as discussed in this post on menstruation by Sara Read.

Jennifer Evans introduced us to William Drage, a man unimpressed by his fellow seventeenth century physicians, including Lazare Rivière, whom, Elaine Leong tells us, was widely read throughout Europe. I wonder what Drage would think of modern doctors, who themselves appear to be looking to the past if Alun Withey’s news of the return of the leech is anything to go by.

Hair loss is a timeless concern and William Drage saw it arising from a “want of good Humours, or an Hectick dry state”, noting that “Eunuchs, because they are more moist, never are bald”. If that makes you squirm in your seat, you might prefer to look at Helen King’s recently-found great-grandmother’s remedy. But perhaps you suffer not from baldness but from the “troublesomnes of Fatnes”? Jennifer Evans offers some early modern cures and I was particularly impressed with the regimen dispensed by Franciscus De Le Boe (hey, great name!).

So far this section has focused on human ailments – but what of dogs? In ‘The Sex Life of Dogs’, Lisa Smith notes the parallels in advice given for dogs and humans in respect of fertility and venereal disease; and in a second post looks at health recipes for dogs, who, like humans, needed to keep their humours in balance. But dogs didn’t have the field to themselves, Jennifer Wallis shows that horses too might yield information that could be extrapolated to humans.

Want to know more about humours and their classical origins? Take a look at this post by Caroline Petit on the Roman physician, Galen, and making his work available in the twenty-first century. Or possibly you’ve had enough of trying to keep your humours in balance and your mind’s set on a “small” beer – James Sumner advises on the abv.

Three sheets to the wind

The captain’s always eager to hear news of his Royal Society colleagues, and indeed entertained them recently with specimens brought back from his first voyage. Elsewhere, Felicity Henderson provided a two-part look at Robert Hooke’s contacts among London’s artists and craftsmen (part 1 and part 2), and Hans Sloane made a cameo appearance in Lisa Smith’s report of a skittle-ground incident in which a man was killed by a unicorn horn (yes, really). While Anna Marie Roos wrote about Martin Lister and the shell collection of Hans Sloane, part of which is in the Natural History Museum and includes shells used by Lister’s daughters, Anna and Susannah, for their illustrations.

On 12 April 1682, John Evelyn FRS recorded this entry in his diary:

I went this Afternoone to a Supper, with severall of the R: Society, which was all dressed (both fish & flesh) in Monsieur Papins Digestorie; by which the hardest bones of Biefe itselfe, & Mutton, were… made as soft as Cheeze… This Philosophical Supper, raised much mirth amongst us, & exceedingly pleased all the Companie”.

Now I love the idea of a “Philosophical Supper” and so was electrified – literally – to read this post by Romeo Vitelli about a “Party of Pleasure” held by Benjamin Franklin, at which the food was cooked by means of – well, you’ll just have to read the post…

Squaring the ratlines

As a ‘future’ professor of geometry, Captain Halley couldn’t resist this look at Euclid’s fifth postulate, the parallel postulate, by Thony Christie. Elsewhere, Kirsten Walsh considered ‘phenomena’ and ‘experiments’ in Newton’s Opticks and Principia here and here, and prompted by Simon Schaffer’s recent BBC4 programme on automata, Will Thomas took a closer look at his article ‘Machine Philosophy: Demonstration Devices in Georgian Mechanics’ here and here.

Eric Scerri noted how the periodic table has penetrated popular culture and that it was 100 years since Henry Moseley discovered that atomic number best captured the identity of an element, rather than atomic weight. Roy Livermore paid tribute to Britain’s greatest rock stars – the geologists whose paper heralded the theory of plate tectonics, which explains Earth’s most important geological phenomena. While Keith Moore wrote about a dating controversy arising from fossils found at Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania.

Human flight has long held fascination, and there have been many schemes over the centuries, including from Leonardo da Vinci, whose Codex on the Flight of Birds has itself travelled widely (and in pieces) before landing intact for a short exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum – Peter Jakab sketches the trajectory. Meanwhile, in London, Becky Honeycombe wrote about the Frost ornithopter, one of the ‘wonderful things’ of the Science Museum.

Floggin’ the oggin

The captain isn’t planning to go sight-seeing during his voyage, but if he were I bet the ‘Disturbingly Informative’ Mütter Museum with its vast collection of body parts would attract his attention. Thanks to Vanessa Heggie for that one, and for directing us to the British Society for the History of Science’s online Travel Guide – despite it being strangely silent on the southern latitudes we’re headed for. I wasn’t too surprised to find Sir Hans Sloane popping up on the site, given he was frequently sought as an adviser and patron of scientific and commercial expeditions, as Matthew De Cloedt explains.

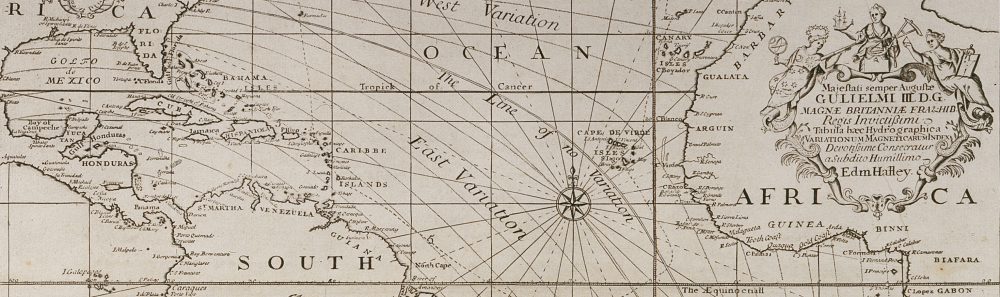

Few words excite Captain Halley more than ‘longitude’ and so Rebekah Higgitt’s trio of posts were right in his line. First Becky marked the 250th anniversary of the famous sea trial of 1763 in ‘Barbados or bust: longitude on trial’, then took a closer look at Christopher Irwin’s marine chair, and lastly considered the changing nature of the post of Astronomer Royal in the wake of Lord Rees’s address at the British Science Festival. We also heard from the Cambridge Digital Library that National Maritime Museum print works have now been added to their Board of Longitude site – hurrah!

It’s a long way to the Terra Incognita (wherever the hell that is), so it’s wise to pack a big book in your sea chest. There are several options for the histsci-inclined seaman, both fiction and non-fiction. For those of a novelistic bent, Carl Zimmer’s essay on the science in Moby Dick makes Melville’s tome one suggestion, and James O’Brien’s look at the scientific methods of Sherlock Holmes offers another. Or if you prefer to spend your R&R with non-fiction, The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Darwin and Evolutionary Thought is “stunning” according to Michael Barton, or you might favour The Society of Useful Knowledge, reviewed here by Laura Snyder, or how about From Books to Bezoars, a book of essays about British Museum founder Sir Hans Sloane, reviewed by Paula Findlen. There are also two lengthy picture posts from BibliOdyssey on Comet Sketches and Map Monsters, and further diversion offered by these videos from the recent ICHSTM conference in Manchester.

So you’ve got your big book and you’re having a sneaky sit down in the marine chair with your noggin of rum – what’s the one thing you’re missing? A hat, of course, to keep off the sun – and what you need is this ‘solar hat’, designed originally for the army in India but just as useful on a ship, where its tiered-design, Antonia Moon tells us, will allow you “to move smoothly through high winds”. Perfect!

Here be dragons

As a former editor of the Philosophical Transactions the captain tells me that no edition was ever complete without some curiosity of nature (or monster), and so here for your delectation are some observations upon a monstrous head (scroll down to page 2 and don’t miss the illustration at the end).

While few editions failed to include one or more papers by the captain, so here’s his charming report of an extraordinary hailstorm that fell in Chester in 1696.

But now the tide’s beginning to turn and the captain’s given the order to weigh. Our course is set for the Terra Incognita, so wish us bon voyage as we set sail on our second Voyage of Discovery – which you can follow ‘live’ @HalleysLog.

We’ll be back in a year! (Probably.)

It’s rather more certain that Giants’ Shoulders will return next month, hosted by Romeo Vitelli at Providentia. As ever, posts should be submitted either directly to the host or to Thony Christie at The Renaissance Mathematicus by October 15.

Don’t forget Giants’ Shoulders always needs hosts, so if you’d like to host the “greatest history of science carnival this side of Alpha Centauri” (T Christie), please contact Thony to agree a month.

_______________

IMAGE CREDITS

The North-West Prospect of Deptford, in the County of Kent (1739): National Maritime Museum, Image PY9727

Battle of Öland in 1676: Nederlands Scheepvaart Museum, Amsterdam (via Wikipedia)

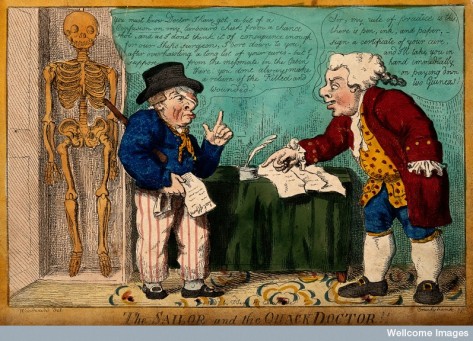

A sailor with a bandaged eye consulting a quack doctor (1807): Wellcome Library, Image ICV No 11266

Mercator map of the world, 1606: National Maritime Museum, Image F0410

Pingback: We are sailing: Giants’ Shoulders #63: Live from Deptford | The Renaissance Mathematicus

Pingback: Carnivalia — 9/11 – 9/17 | Sorting out Science